Breaking the Rules-Based Order

Iran’s survival outside U.S. finance and military command challenges the logic of empire and exposes the violence used to preserve it.

A quiet war just became a loud one.

After years of sabotage, sanctions, and shadow strikes, Israel and the United States have taken their campaign against Iran into the open. First, Israel launched direct attacks on power stations, infrastructure, and nuclear sites deep inside Iranian territory. At least 430 people have been killed and 3,500 injured. Blackouts ripple through cities like Isfahan and Natanz.

Then, on June 21, President Trump confirmed that the U.S. had launched their own assault, sending B-2 bombers to strike Iranian nuclear enrichment sites. He also warned that retaliation would be met with “force far greater than what was witnessed tonight.”

What was a campaign of pressure has become a war.

Israel struck first. The United States has now followed their lead. The question now is why Iran was targeted in the first place.

Because this isn’t about nuclear weapons. Or religion. Or irrational ideology.

This is about imperialist structure.

Iran is one of the few countries in the world that has resisted integration into the U.S.-led financial order. Since 1979, it has operated a political economy largely insulated from Western capital: centered on state-owned industries, parastatal firms, domestic manufacturing, and strategic subsidies. Foreign capital doesn’t own its oil fields. U.S. corporations don’t control its infrastructure. It doesn’t take IMF loans, and it doesn’t peg its economy to the dollar.

That kind of independence is intolerable to the U.S. capital class.

Iran is not a socialist state, but it is a sovereign one. And in a global system built to punish disobedience, sovereignty itself is a threat.

This essay is not about defending Iran’s government. It’s about understanding what Iran is materially, structurally, and historically, and why the U.S. and Israel are trying to break it now. We’ll trace how Iran’s political economy emerged from revolution and war, how its energy and security strategy reflects the limits of autonomy under siege, and how its contradictions, internal and external, have shaped the crisis we’re watching unfold.

The Coup That Closed the Door

Before the revolution that culminated in the current Islamic Republic, there was another Iran and another possibility.

In the early 1950s, Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh led a broad nationalist movement to take control of Iran’s oil from the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now BP). Backed by the parliament, a growing middle class, and much of the public, Mossadegh nationalized the industry and proposed a vision of Iranian development that was democratic, secular, and independent of foreign capital.

British capital’s revenue and assets were threatened, and after Eisenhower was elected, the UK was able to enlist the help of the U.S. Because Mossadegh’s success would have set a dangerous precedent: an oil-rich nation asserting control over its own resources outside the Western order.

In 1953, the CIA and MI6 orchestrated a coup that overthrew Mossadegh and reinstalled the Shah. His return marked the beginning of a new political economy: one based on oil revenue, U.S. military aid, and rapid industrialization under foreign guidance. Iran modernized, but in service of a model designed to benefit elites, foreign investors, and Western strategic interests.

By the late 1970s, inequality had deepened. The working class had grown, but remained politically suppressed. The clerical establishment, which had largely been sidelined by modernization efforts, stepped into the vacuum. And when the revolution came, it came not as a continuation of Mossadegh’s vision, but as a reaction to the world that destroyed it.

Had Mossadegh’s path been allowed to continue, Iran may well have evolved into a liberal petro-state: formally democratic, structurally dependent, and ultimately aligned with the West. Something closer to post-colonial India or Indonesia. Sovereign in name, but governed through foreign capital and domestic technocrats. In the long run, this would have served U.S. interests. But capital does not operate on the logic of long-term stability. It responds to threats in the present. So the U.S. crushed a government that could have become a client, to protect the principle that no challenge to capital can go unanswered.

By shutting that door, it opened another. The U.S. created conditions for something far more volatile: decades of repression, ideological polarization, and eventual revolt. The revolution of 1979 wasn’t inevitable. It was the consequence of an empire that refused even moderate autonomy, then punished the result of that refusal.

Like what you’re reading?

Subscribe here for weekly essays that challenge power, not just critique it.

How the Revolution Reshaped Iran

The Shah’s post-coup regime, propped up by U.S. weapons and oil money, pursued rapid industrialization without redistribution. Oil wealth flowed into elite hands. Foreign firms controlled key industries. A growing urban working class labored under repressive, top-down rule while the rural poor were displaced by uneven land reforms and mechanization. Political dissent had been violently suppressed, especially on the left.

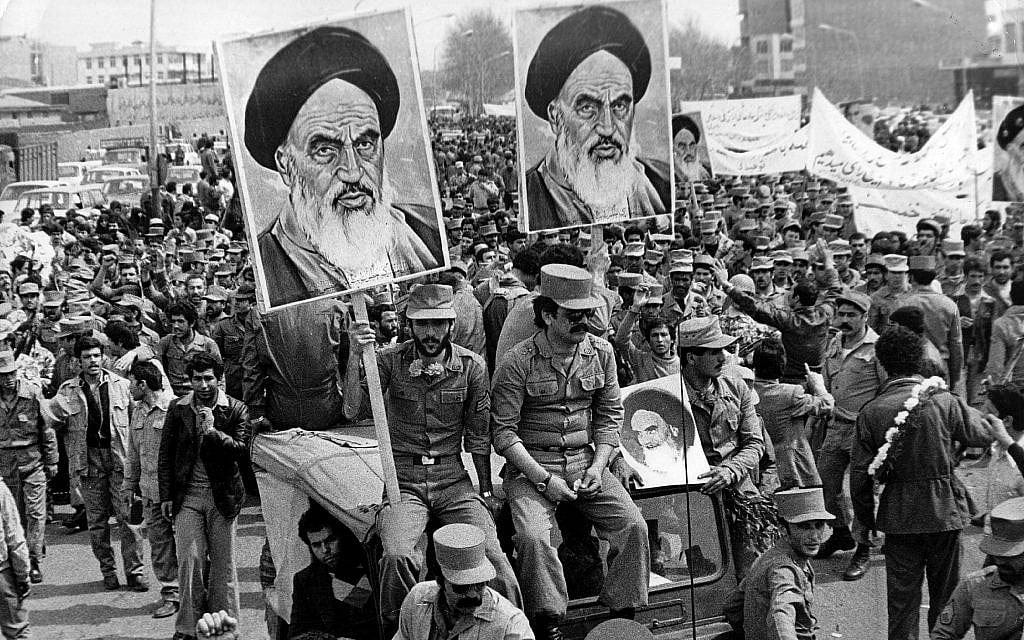

But the discontent was also nationalistic. The 1953 coup remained an open wound. The Shah was widely seen as an imperial puppet. By the time revolution broke out in 1978, it wasn’t driven by a single class or ideology. Secular nationalists, Marxist parties, student radicals, bazaar merchants, the rural poor, and the clerical establishment all opposed the regime for very different reasons.

In early 1979, the direction of Iran’s future was still contested. Some wanted a return to constitutional democracy. Others hoped for socialism. But the clerical leadership, organized through the mosques and embedded in networks of charity and moral authority, moved quickly to consolidate power. With the left purged and the monarchy dismantled, Ayatollah Khomeini and his allies claimed the revolution as Islamic.

But ideology alone couldn’t govern a country on the brink. What emerged in the 1980s was a political economy of survival. With the U.S. severing ties, foreign capital fleeing, and Iraq invading, the new regime rapidly centralized control over industry, infrastructure, and redistribution. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), originally founded to protect the revolution, expanded into construction, oil, and telecom. Religious foundations (bonyads) were granted vast landholdings and took over industries once held by royalist or foreign firms.

In theory, these institutions redistributed wealth to the poor. In practice, they created a new power bloc: a bureaucratic, militarized bourgeoisie rooted in the state.

The working class was valorized, but never empowered. Political dissent was equated with treason. And through war, sanctions, and repression, Iran’s new order was born: a theocratic state, economically independent from the West, yet internally hierarchical and centralized under clerical-military rule.

Unlike many of the countries the West demonized during the Cold War, it was not socialist.

But it was sovereign, and that made it dangerous.

Iran’s Political Economy of Survival

The war with Iraq devastated Iran’s infrastructure and cemented the contours of its political economy. Cut off from Western capital, under mounting sanctions, and facing an existential military threat, the new regime constructed an internally coherent system designed not for growth but for survival.

That system wasn’t capitalist in the Western sense, nor was it socialist. It was something more contradictory: an insulated economy with almost no foreign ownership, dominated by religious and military institutions that claimed to represent the people, but functioned without their consent.

The IRGC expanded into a sprawling economic network. Its construction arm, Khatam al-Anbiya, now controls infrastructure, energy, mining, and logistics contracts worth tens of billions. Meanwhile, bonyads over 120 tax‑exempt, Supreme Leader‑controlled foundations, took over entire sectors of agriculture, manufacturing, and housing. Both are exempt from taxes and political oversight. Together, they now account for as much as 60% of Iran’s economy.

Foreign investment is nearly nonexistent. Since 1979, Iran has remained off-limits to U.S. investment, heavily sanctioned by Europe, and increasingly reliant on state-to-state barter with China, Russia and Venezuela. Its revenue is channeled not into multinational profits but into military spending, domestic subsidies, and large-scale infrastructure. In this way, Iran has maintained a form of sovereignty that is increasingly rare in the global South: a national economy largely insulated from Western capital.

The Ruling Bloc

Iran’s dominant class is not a traditional capitalist elite, but a bloc of interlocking institutions that consolidate power across military, religious, and economic lines. At the top sits the Supreme Leader and the clerical establishment, whose authority is reinforced by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). A military force with vast economic holdings and deep influence over foreign and domestic policy. Alongside them are the bonyads, powerful semi-private foundations that control key sectors of the economy, often shielded from public accountability.

Tied to these institutions is a domestic bourgeoisie: business owners, contractors, and financial elites who profit through state connections rather than market competition. Their interests are tied to the survival of the regime, which guarantees their monopolies, protects their wealth from foreign competition, and suppresses labor unrest. Together with senior bureaucrats, conservative judges, and ideological managers in education and media, these groups form a ruling class whose primary goal is not free market capitalism but the preservation of a nationalist political economy built around sovereignty, hierarchy, and resistance to imperialism.

The Working Class

The Iranian working class, roughly 45% of the population, has no real leverage over the economy it sustains. Manufacturing accounts for approximately 21% of GDP (compared to roughly 10% in the U.S.), but despite their centrality, many workers are employed informally in precarious roles. Workers are also heavily concentrated in construction, transport, and the public sector - often hired informally or through exploitative contracts. Even in strategic industries like oil and gas, where workers occasionally win modest concessions, strikes are suppressed and independent organizing remains illegal. Across these sectors, labor is vulnerable, fragmented, and structurally isolated from political influence.

The Rural Poor and Quasi-Peasantry

Meanwhile, about 14% of Iranians still work in agriculture, with many concentrated in peripheral provinces like Khuzestan, Kurdistan, and Sistan-Baluchestan. These rural workers often live under quasi-peasant conditions: small landholdings, limited market integration, vulnerability to drought, and limited access to state services. While not serfs, their subsistence livelihoods leave them economically and politically marginal.

These rural communities form a politically sensitive group. They are often religiously conservative and materially dependent on state subsidies or IRGC-run infrastructure projects. Like the rural populations under Tsarist Russia, they are not a revolutionary class, but a stabilizing one: absorbing hardship, reinforcing ideological legitimacy, and helping to blunt the influence of urban protest movements. The regime governs them through managed dependency: ensuring just enough provision and symbolic respect to discourage rebellion.

While urban workers push for labor rights and educated youth demand reform, these rural populations are shielded from political agitation and positioned as the regime’s moral and material ballast.

The Fragmented Middle and Youthful Unrest

Between the ruling bloc and the working poor lies a fragmented middle: shopkeepers, service workers, petty traders, and a broad stratum of state-employed professionals: teachers, engineers, and bureaucrats. Most lack formal protections, but also avoid open confrontation. Economically tethered to state institutions yet excluded from real power, many default to political caution, shaped by religious conservatism, material necessity, and the trauma of past instability.

Within and around this middle layer is a rising cohort of disillusioned youth: educated, underemployed, and alienated from both the regime and the official opposition. They have fueled waves of protest and civil disobedience, but their efforts remain ideologically scattered and organizationally isolated. Without ties to either the state or the traditional opposition, they float between social strata. Too marginal to lead, too restless to disappear.

In different ways, the rural poor and fragmented middle serve as buffers: one through religious and material dependency, the other through economic entanglement and political fatigue. Youth unrest cuts through these layers, but without structural coherence, it burns hot and fades fast.

Prolonged siege, rationalized as a defense of human rights and democracy, has reshaped Iran’s economy, creating both the conditions and justification for its internal architecture of control.

The state governs by managing the divergent needs, loyalties, and material conditions of each class: isolating urban and youth unrest, pacifying rural conservatism, and fragmenting the middle. No single group can challenge the system alone, and the system ensures they never unite. Subsidies and repression, appeals to religion and threats of treason, selective inclusion and targeted exclusion: all are deployed to keep resistance compartmentalized and cross-class alliances unthinkable.

Gender, Reproduction, and the Boundaries of Resistance

No group embodies the contradictions of Iran’s political system more than women.

Women make up nearly half the population, but account for only around 14% of the formal labor force. Their exclusion is religious and ideological. The Islamic Republic rests on a vision of gendered order that centers the woman as mother, moral anchor, and symbol of cultural purity. State policy reinforces this through mandatory veiling, gender segregation, and employment codes that either push women out of the workforce or confine them to teaching, nursing, and clerical roles.

But this ideological control does not fully translate into material dependence. Women in Iran are among the most educated in the region: the majority of university graduates are female, and women dominate certain academic fields. This contradiction between education and exclusion has produced one of the most explosive dynamics in Iranian society.

Women have played leading roles in every mass uprising of the last two decades, including the most recent movement sparked by the killing of Mahsa Amini in 2022. These mobilizations are not only about gender; they’re about the authority of the state, the legitimacy of clerical rule, and the social order that props up both.

Crucially, women’s economic marginalization also weakens collective power. Excluded from many workplaces and locked into informal or care-based labor, women are often denied access to the kinds of organizing spaces where worker consciousness forms. And yet, their role in social reproduction: raising children, managing households, and navigating rationing systems makes them central to both the daily functioning of society and the legitimacy of the regime.

Gender repression serves both ideological and material purposes: it reinforces the regime’s religious authority, defines its image of moral order, and helps regulate labor, education, and public space. By excluding most women from the formal economy and policing their presence in public life, the state limits potential sites of political convergence and maintains a hard line between sanctioned identity and organized dissent.

These gendered controls are embedded in the same apparatus that disciplines workers, isolates rural populations, and fragments opposition. Gender policy in Iran is inseparable from its broader model of survival: a model that secures sovereignty by tightly managing the contradictions within. One that ensures no broad alliance can challenge the state from within while it’s targeted from without.

The Nuclear Program as Political Economy

Iran’s domestic economy is structured for survival under siege. Its nuclear program is the global expression of that same logic. Whether or not Iran builds a weapon is not the central issue. What threatens the current order is the idea of a nation developing strategic independence, without Western permission.

A deep hypocrisy lies in who is allowed to have such weapons. Israel possesses an undeclared nuclear arsenal and has never signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty. The U.S. not only has the largest stockpile in the world, it remains the only country to have ever used nuclear weapons. Yet it is Iran, despite being isolated, sanctioned, and surrounded, that is cast as the existential threat. In this context, Iran’s nuclear capacity, real or potential, is a rational deterrent. A signal that domination will carry a cost.

Iran’s pursuit of nuclear energy began decades before the Islamic Republic. Under the Shah, it was materially supported by the U.S. as a modernizing project. After the revolution, it became something else entirely: a national strategy to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, withstand sanctions, and build long-term scientific and industrial capacity under conditions of isolation and embargo.

That strategy fits neatly within Iran’s broader political economy. Its nuclear program could power domestic industry, reduce reliance on oil exports, and develops a scientific class, all without foreign capital or corporate ownership. In a country locked out of global finance, every step toward self-sufficiency becomes a strategic act.

Mastering uranium enrichment also offers a form of deterrence essential for survival in a hostile geopolitical environment. It complicates military intervention, strengthens Iran’s role as a sponsor of anti-colonial resistance, and makes regime change less likely. It reinforces a long-standing message: we will not be governed by your conditions.

The Iran Nuclear Deal

The 2015 nuclear deal (JCPOA) briefly offered a different path: sanctions relief in exchange for limits on enrichment and increased inspections. Iran complied. Trump walked away under pressure from Israel and the American right, who saw any compromise with Iranian sovereignty as a strategic failure.

When the deal collapsed, Iran resumed enrichment not as an act of aggression, but as a return to its default posture: building deterrence under siege.

In 2021–24, Biden had opportunities to rejoin the deal, but the U.S. expanded their demands, aligning more with Israel’s agenda than with returning to the original framework.

Then in April–June 2025, Iran entered a 60-day negotiation window with the U.S., prompted by Trump, and was set to meet negotiators just days after Israel’s strikes began, which killed several high-level Iranian nuclear scientists and military leaders, including Ali Shamkhani, a top advisor participating in those talks. The timing was not accidental: Israel launched its largest-ever attack on Iranian nuclear sites while international diplomacy was in play, using the 61st day as a strategic launch point.

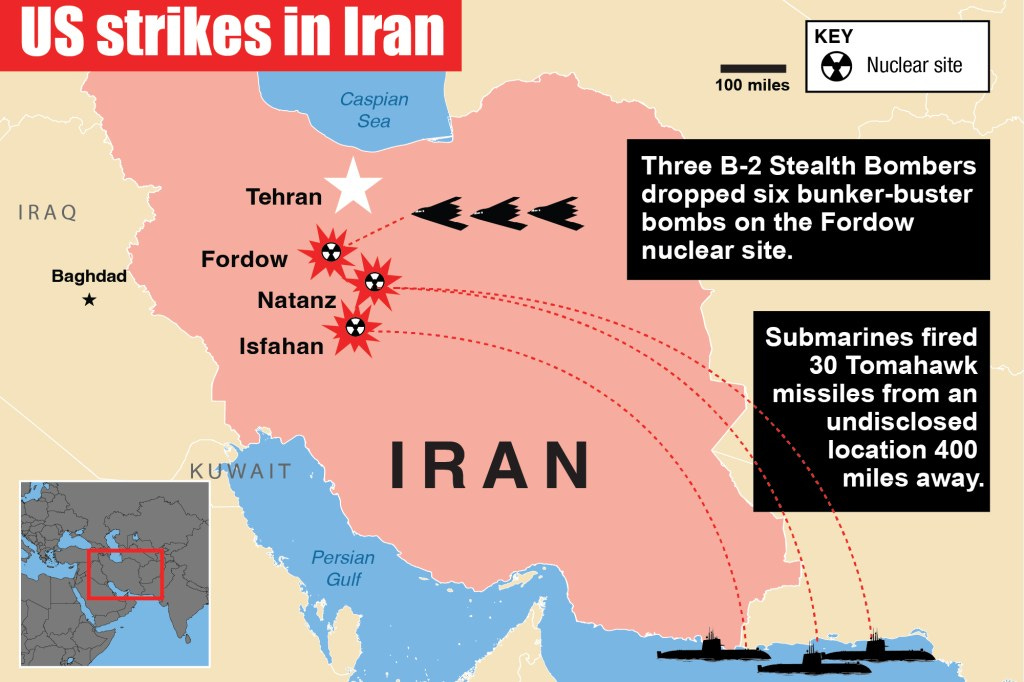

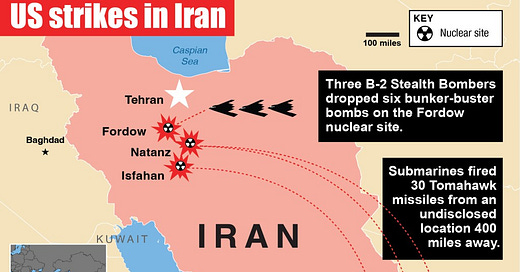

On June 21, just days after Iranian officials confirmed their willingness to continue nuclear talks, the United States launched its largest direct assault on Iran to date. In coordination with Israeli intelligence, B‑2 stealth bombers and submarine-launched Tomahawk missiles targeted three nuclear enrichment facilities: Fordo, Natanz, and Isfahan. Pentagon sources described it as the largest B‑2 deployment in U.S. history, involving more than a dozen bunker‑buster bombs and dozens of cruise missiles.

President Trump celebrated the attack as a “spectacular military success,” claiming Iran’s enrichment capacity had been “totally obliterated.”

It was also illegal under international law, a violation condemned by diplomats and legal scholars across the world.

Tehran has since launched missile and drone strikes in response, targeting Israeli territory and causing multiple injuries. But the global narrative, shaped by media aligned with U.S. interests, continues to frame Iran as the aggressor.

The Iranian nuclear program is a structural response to a structural condition. In a world where development is only permitted through Western channels, Iran’s self-directed path, scientific, strategic, and sovereign, is what truly makes it dangerous.

Israel’s Strategy, and Why Iran Must Fall

Israel’s campaign against Iran is strategic, preemptive, and long in the making.

For over a decade, Israeli officials have framed a nuclear-capable Iran as an existential threat. But this obscures the real concern: that Iran will enable others to resist Israel. Through funding, training, and logistical support, Iran has played a central role in sustaining the only military forces in the region that have meaningfully challenged Israeli aggression: Hezbollah in Lebanon, armed groups in Gaza, and militias across Iraq and Syria. These are material relationships, built on real infrastructure, weapons development, drone technology, tunnel construction, and battle-tested strategy.

In Israel’s eyes, that makes Iran the cornerstone of an entire axis of resistance. And as the war on Gaza has escalated, so too has the urgency to break that axis.

This is the context for the strikes in 2025. They are an intentional effort to collapse any chance of diplomacy. Talks between Iran and the U.S. had resumed. And just as the next round of those talks neared, Israel assassinated key negotiators and launched its largest attack on Iranian nuclear infrastructure to date.

The timing also plays a strategic role for Israel beyond nuclear talks.

Since October 7, 2023, the war in Gaza has turned global opinion against Israel’s war doctrine. Lebanon remains volatile. The Houthis have disrupted Red Sea trade. Iraq and Syria are no longer passive corridors for Israeli or U.S. power projection. And despite normalization efforts with the Gulf states, public opinion across the Arab world remains deeply opposed to Israeli policy. The regional map is shifting, and Iran remains the only actor providing sustained, material opposition to Israeli dominance.

From Israel’s perspective, that window must be closed now before multipolarity hardens, before Palestinian resistance regroups, before a new Middle East emerges that it can’t control.

And so it strikes to force a crisis.

To draw the U.S. deeper into confrontation. To end diplomacy. To redefine the terms of resistance, and destroy its material foundation, before it’s too late.

The Regime Change Blueprint

What Israel enacts through military strikes, the U.S. has long pursued through political warfare. Sanctions, sabotage, media operations, and NGO funding form a decades-long campaign to dismantle Iranian sovereignty itself.

The blueprint is familiar. First, isolate the country economically: cut it off from trade, seize foreign reserves, lock it out of international finance. Then fund media and civil society groups to shape internal opposition. Amplify tensions. Weaponize discontent. If protests emerge, frame them as democratic uprisings. If repression follows, use it to justify further escalation.

Iran is not immune to these pressures. Inflation, corruption, and factional infighting have all undermined the government’s legitimacy. But U.S. policy is not designed to empower the Iranian people; it’s designed to punish them into rebellion. Sanctions don’t just target elites; they crush workers, inflate food prices, and weaken basic infrastructure, making daily life more precarious for the very people Western media claims to support.

At the same time, the ideological core of the state adapts. It uses the permanent threat of regime change to justify repression, suppress labor organizing, and discipline dissent. Every strike or protest is seen as a foreign plot. Crackdowns become national defense. Survival becomes justification.

To recognize this is not a defense of Iran’s rulers. The political economy of survival under siege breeds a feedback loop: foreign pressure tightens domestic control, and domestic control reinforces foreign pressure. A true democratic opening, one grounded in material redistribution and national self-determination, becomes nearly impossible under these conditions.

Multipolarity, the Closing Window, and the Next Phase of Resistance

Washington and Tel Aviv are watching the world slip out of their hands.

BRICS expansion now links China, Russia, Iran, and Saudi Arabia in energy swaps that bypass the dollar.

De-dollarisation experiments, from rupee-ruble trade to China’s digital yuan pilots, chip away at the U.S. ability to weaponise payments.

Disruptions in the Red Sea, Hezbollah’s drone capabilities, and the growing reach of Iranian missile technology through militias in Iraq and Syria all reveal how asymmetric actors are reshaping the balance of power and increasing the cost of regional intervention.

If this trend continues, Iran’s survival will look more like a template than an anomaly. From the U.S. and Israel’s perspective, the time to strike is now, before alternate financial rails, hardened alliances, and non-Western weapons networks render “maximum pressure” obsolete.

Iranian drones appear in Gaza workshops. Tehran and Caracas trade diesel for wheat outside the dollar. Yuan-denominated oil is used for infrastructure in Africa. Each transaction chips away at sanctions enforcement. South Africa’s legal case against Israel at the ICJ, backed by evidence from multiple states, has pushed the genocide framing into official discourse. Meanwhile, over 140 countries now recognize Palestine as a state, many reaffirming or expanding that recognition since the war on Gaza intensified.

What Multipolarity Makes Possible

Even the ideological terrain is shifting. The war on Gaza has shattered the illusion that U.S. power guarantees stability. Iran’s survival, contradictory as it is, demonstrates that states outside the “rules-based order” can endure and even project power.

None of this makes Iran a liberatory model. Its political economy remains repressive and centralized. Multipolarity doesn’t erase class struggle or patriarchal rule. But it does create breathing room. Strategic space in which workers, feminists, and national-liberation movements from Beirut to Bogotá may have more room to move.

The key questions now are whether China will insure Iranian shipping or invest in energy corridors that make sanctions unenforceable; whether Gulf monarchies will hedge their bets, quietly trading with Iran while purchasing U.S. air-defense systems; and whether emerging labor and feminist movements inside Iran can take advantage of the cracks that outside pressure no longer easily seals.

Multipolarity doesn’t guarantee emancipation. But it reopens the possibility of historical agency, a chance to fight for more than the right to be a client state. And it is precisely that possibility that Washington and Israel are racing to shut down.

Why This Matters

Iran is not an ideal society. Its government is repressive, and its political economy concentrates power in military and religious institutions. But that’s not why it is under attack.

It is under attack because it has remained sovereign economically, politically, and militarily in a world where sovereignty is conditioned on U.S. approval.

Iran controls its oil. Builds its defenses. Trades outside U.S. systems. And supports others who resist.

This war is about what Iran represents: the possibility of defying a system built around the interests of capital.

The strikes, the sanctions, the isolation. None of it is random. It’s a strategy meant to preserve a global order where only certain states get to be powerful, and the rest are expected to align or collapse.

Reject the logic that says only one kind of development, one kind of power, one kind of future is acceptable. And recognize who pays the price when that logic is enforced.

Understand the world. Change the world.

You’ve read this far for a reason.

You’re not here to be comforted; you’re here because something isn’t adding up.

Let’s figure it out together.

Weekly essays from Concrete Analysis.

Direct. Unapologetic. Grounded in reality.

This piece made you think? Help others see it too.

Share this post

Further Reading

These works offer deeper political grounding for understanding Iran’s role in the global system, not as a rogue state, but as a challenge to imperial hegemony. They are divided into liberal critiques that expose the hypocrisy and violence of U.S. and Israeli policy, and Marxist foundations that trace the roots of resistance, revolution, and political economy in Iran and beyond.

Liberal Critiques

The Twilight War by David Crist

A detailed account of the covert conflict between the U.S. and Iran since 1979. Often framed through a U.S. national security lens, but offers crucial insight into how long this war has been quietly waged.All the Shah’s Men by Stephen Kinzer

A gripping narrative of the 1953 coup that overthrew Iran’s elected leader. Told accessibly, and useful for understanding how U.S. intervention shaped everything that followed.

Marxist Foundations

Socialism or Anti-Imperialism? by Valentine Moghadam

Traces how Iran’s revolution was shaped and limited by the contradictions between leftist aspirations and Islamist consolidation. A sharp historical analysis that doesn’t pull punches.A Social Revolution: Politics and the Welfare State in Iran by Kevan Harris

Dissects the hybrid nature of Iran’s political economy, from bonyads to sanctions resistance. Harris’s work bridges sociology and material analysis without liberal moralizing.

Up next: Tuesday, I’ll be posting a short follow-up on the alliances that make Iran dangerous to empire, and how the West uses “contradictions” to discredit every movement that fights back.

Subscribe to be notified when it drops.

If something in this piece resonated or challenged you, I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

Thanks for reading! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Thanks for reading. I’ll be posting a short follow-up on Tuesday about how Iran supports regional resistance movements, and why that support is treated as a threat.

I would love to hear your thoughts or questions below.